|

His Emperor's Reluctant Warrior

Reprint from The Japan Times By DAVID MCNEILL |

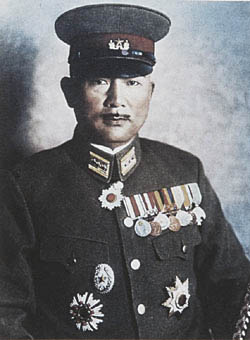

General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, commander of Japanese forces on Iwo Jima PHOTO COURTESY OF SHOGAKUKAN |

Samurai-born and steeled in Japan's harsh military culture, Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi had lived five years in North America but was largely unknown to Washington's leaders when he was ordered to defend Iwo Jima "at all costs." The U.S. would pay dearly for underestimating him.

|

The U.S. would pay dearly for underestimating

him

|

In the summer of 1929, he must have been an odd sight: a middle-aged Japanese man driving alone across the American Midwest in a Chevrolet, drawing spindly sketches of the people and places he saw. |

Beneath the bucolic calm of the endlessly rolling farmland, though, dark forces churned unseen: the Great Depression loomed just weeks away, East Asia simmered uneasily with the conflict that would soon rip the region apart, and in Europe an unknown Austrian artist was building the foundations of the Nazi Party.

But 38-year-old Tadamichi Kuribayashi, who would become one of Imperial Japan's most implacable generals, was at peace with the world, stopping and chatting randomly to children, and writing happily to his family about America's vast open spaces, its freedoms and tough, resilient people.

"Taro, listen to your mother like these American children," he told his eldest son in one letter home after praising the caution of youngsters who had refused his offer of a lift in the Chevrolet. "They obey their parents and know right from wrong."

To his wife -- left at home in Tokyo when he was posted as a military attache to the Japanese embassy in Washington the year before -- he sent pictures he drew of children wearing the baggy denim overalls of the day, telling her to make them for his own family. To his son, he offered the simplest of advice: "Be kind to others, it is the most important thing in life."

| Fifteen years later, this affable visitor would command a fearsome military machine dedicated to mowing down the same farm boys he met in Kansas, Iowa and Kentucky. And although he was one of the few men |

. . . in five weeks of fighting there, killing

nearly one third of all the U.S. Marines who died in World War II.

|

Plucked from the ranks of the army's dwindling corps of senior officers by Emperor Hirohito, the general ferociously defended his country against its first foreign invasion with a tactically brilliant defensive strategy that revolutionized warfare. When it was over, most of the accolades came from the enemy.

"Of all our adversaries in the Pacific, Kuribayashi was the most redoubtable," said Gen. Holland "Howlin' Mad" Smith, who led the assault on Iwo Jima. The soldiers under his command were less eloquent but no less respectful, dubbing their nemesis, "The best damn general on this stinking island."

|

"Of all our adversaries in the Pacific, Kuribayashi

was the most redoubtable"

|

The warrior Japan chose to lead this fight to the last in the spring of 1945 was a mercurial, contradictory man: a samurai descendant and loyal servant of the Emperor who detested much of Japan's authoritarian, |

"The United States is the last country in the world Japan should fight," Kuribayashi wrote in a letter home days before his doomed forces inflicted massive casualties on U.S. forces landing on the 22.4-sq.-km (7-sq.-mile) island.

|

The tensions in Kuribayashi's character, and his reluctance to go to war with the U.S., slowed his rise through the ranks of Japan's military, says grandson, Yoshitaka Shindo. "My grandfather was sidelined because he didn't fit in with military thinking. He had friends in America and respected the country." According to colleague Army Capt. Kikuzo Musashino, "The general spoke about his years in America, saying they had enormous industrial resources. He said: 'When war comes, they can convert all that ability into military use. The people who planned this war in Japan know absolutely nothing |

General Kuribayashi (seated, center) with officers and men under his command during preparations for their doomed defense of Iwo Jima PHOTO COURTESY OF THE KURIBAYASHI FAMILY |

Kuribayashi's links with the U.S. began when he was sent as a deputy military attache to Washington in March 1928. Over the next three years, he traveled extensively around the country -- awestruck at every turn by its "huge industrial potential" and "energetic, versatile people."

An inveterate scribbler who hated being apart from his wife and two young children -- Taro (born 1924) and Yoko (1928) -- Kuribayashi wrote hundreds of letters to Tokyo, filling them with chatty observations. "They always eat the same things here: sweet corn and potatoes. How luxurious Japan is by comparison," he sniffed in one letter. American women, so different to their demure, obedient Japanese counterparts, ruffled his feathers. Forced at a party to interrupt his meal to stand and bow every time a woman entered, he wrote: "What nonsense. Why do we have to stand when these lofty females enter as their men cringe behind them?"

| What nonsense. Why do we have to stand when these lofty females enter as their men cringe behind them? | The letters, often addressed directly to his children, continued throughout the 1930s from postings in Canada, Europe and later, as Imperial Japan began its brutal sweep across China, from |

The choice of Kuribayashi to defend Iwo Jima raised eyebrows. Less experienced than many other commanders, and at odds with the top brass over the war, he was hardly the gung-ho Japanese warrior of legend as he watched in despair Japan's blood-soaked retreat from the Pacific theater.

But the time for arguing the merits of the war was gone. As Prime Minister Hideki Tojo told him in May 1944, Japan was fighting for its survival and the tiny tear-shaped volcanic rock -- "a trivial scab," in the words of "Flags of our Fathers" author James Bradley (whose father was one of the Marines in the iconic flag-raising photo) -- had assumed enormous strategic, and psychological, importance

|

If the Americans took the island and its three airstrips, they would halve the flight time of their massive new long-range B-29s from the Marianas and intensify their carpet-bombing of Japanese cities. And Iwo Jima was Japanese soil, with a Tokyo postal address. Allowing U.S. soldiers to plant the Stars and Stripes there would signal Japan's impending defeat. Such was the importance of his mission that the general was granted a rare, farewell meeting with the Emperor the night before he left. Kuribayashi knew he would never set foot on the mainland again. Before departing, he told his wife not to plan for his return, having typically spent his last hours with his family fixing a kitchen shelf. His first letter from the island, written on June 25, 1944, is heavy with foreboding and regret: "This war broke out just as I was thinking I would be able to begin giving happiness to all of you as your husband . and father. But once ordered to defend this most vital |

General Kuribayashi prepares Iwo Jima's defenses. PHOTO COURTESY OF SHOGAKUKAN |

The cosmopolitan man who discussed literature and politics with Washington's finest was gone, replaced with a warrior, conscious of his deep heritage and his duty to his country and ancestors, and newly imbued -- at least in public pronouncements -- with the quasi-fascist, blood-and-soil rhetoric of the era.

On the eve of his departure he wrote to his brother that he would fight with all his strength "as the son of Kuribayashi, the samurai." The Americans in his letters were now kichiku beigun -- "devilish, brutal and cunning," the cause of Japan's looming "national calamity."

He wrote a samurai death poem:

Though I decay into the fields in the midst of our revenge, I will be

reborn seven times to seize my sword.

|

After arriving on Iwo Jima, Kuribayashi hiked

all over the island, rising at 3.30 a.m. every day to survey its

defenses and micromanage preparations for the invasion.

|

Kuribayashi quickly formulated a remarkable, controversial plan: the battle would be fought from beneath the ground. The strategy, closer to the guerrilla fighting later faced by Allied soldiers in Vietnam, reversed the standard battle tactics of Japanese troops who had charged at the |

There were other surprises in the general's preparations. The Japanese artillery would initially stay silent and allow the enemy to come inland 500 meters rather than hitting them wading through the surf as it had in Saipan, Guam, Tarawa and countless other failed engagements. Kuribayashi would then unleash a formidable arsenal of weapons, including more than 400 large artillery pieces, rockets, naval and antiaircraft guns and even tanks, buried or hidden deep in caves, bunkers and man-made tunnels dug into the soft volcanic rock.

Preinvasion U.S. bombardments, including a pulverizing 800-ton bombing raid on Dec. 8, 1944, only hardened the Japanese resolve, sending men and weapons so far underground they were virtually impregnable by the time the first Marines set foot on the island on Feb. 19, 1945.

|

Unlike the horrific Battle of Okinawa from March to June 1945, in which a third of the local civilian population was killed, Iwo Jima was to be a "clean" fight. Kuribayashi expelled the few civilians on the island, instructing the women to wear pants to avoid rape. He refused the offer of "comfort women" -- sex slaves from Korea and Taiwan -- because he abhorred the abuse of civilian populations in wartime. And he even apologized to the locals for causing them trouble and taking their land. Much to his anger, however, his superiors forced him to waste precious time and labor by building standard concrete pillboxes overlooking beaches between Suribachi and the East Boat Basin, which were quickly overrun in the early stages of the battle. Unlike his deskbound bosses, he knew that the deeper underground his men went the longer they would survive, so he drove them relentlessly, digging nearly 20 km (12.43 miles) of tunnels despite poisonous volcanic gases and scorching heat that reached over 50 degrees (122F) His own airless command bunker, 500 meters (546.81 yds) south of Kita Village, was buried 20 meters (21.87yds) underground in walls made of thick concrete. The heat, back-breaking work and mosquitoes and ants on the barren rock were "a living hell" Kuribayashi told his family in letters that |

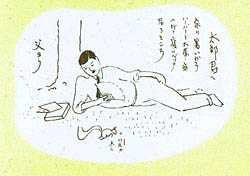

The mouth of one of the countless tunnels Gen. Kuribayashi had his troops dig on Iwo Jima to protect them from enemy bombardments. A self-portrait of Kuribayashi on the Harvard University campus (below) that he sent home to his son Taro in Tokyo NAO SHIMOYACHI PHOTO (above); ILLUSTRATION COURTESY OF SHOGAKUKAN, from "'Gyokusai Soshikikan' no Etegami"  |

"After seven days, my skin is burned black and has peeled off many times," he said, adding that during the fierce U.S. air bombardments, he and his men "could do nothing but hold our breath, praying to God and Buddha in our bunkers."

"We don't know when the enemy is going to land. . . . If the island is taken the Japanese mainland will be air-raided day and night, so our responsibility is extremely high. Everyone is fully prepared to die if necessary."

By the end of the buildup in February, Kuribayashi commanded a force of over 21,000 men, some just boys of 16 or 17, and including both navy and army divisions and conscripted Korean laborers. Altogether, some 95 percent of his force would die on the island. The men, according

|

The Japs weren't on Iwo Jima,

said Capt. Thomas M. Fields of the 26th Marines afterward, they

were in Iwo Jima

|

to the official U.S. Marine Corps history of the battle, were "deeply entrenched" in "masterfully camouflaged" bunkers, blockhouses, pillboxes and caves divided into five sectors. |

"The Japs weren't on Iwo Jima," said Capt. Thomas M. Fields of the 26th Marines afterward, "they were in Iwo Jima."

Kuribayashi quickly realized that the lack of food and fresh water would plague his troops. Every man, including commanders, received a ration of just one canteen a day. The few boats that could reach the island made the most of their visits. "We gave the soldiers . . . all we had, including personal possessions," says Koji Kitahara, then a 23-year-old Japanese sailor who was on one of the last supply runs to the island. "We knew they weren't coming back."

Remarkably, even as one of the greatest naval armadas in history approached,

along with his own certain doom, the general found time to fret over the

trivia of family life. In one letter he gave detailed instructions to

20-year-old Taro on how to complete the shelf-building interrupted by

the Emperor's summons. On Dec. 23, 1944, he told his youngest daughter,

Takako, about chicks that had been born on the island, saying, "They

are bounding about and sometimes fight each other." On Jan. 18, 1945,

he replied to a letter saying that his daughter had scored a string of

As. "Your father is so happy. Keep studying and always get As. But

don't become big-headed. Do not bully or be cynical." Then, in early

February 1945, he fretted that his wife and daughter would catch cold

("take a hot water bottle and keep your waist and stomach warm")

and urged them to get out of Tokyo before the air raids ("they can

completely destroy Tokyo with their bombers") while playing up his

own health. "Almost everyone gets sick here at least once,"

he said, "but I'm happy that I've been well . . . I'm getting quite

fat when I see myself in the bath." It was his final letter home.

When Kuribayashi finally unleashed his forces just after 10 a.m., the

eastern, 500-meter beaches of Iwo Jima were jammed with equipment and

men ready to believe that aerial and naval bombardments had destroyed

the Japanese defenses. Mortars, rockets and bullets rained down as the

volcanic terrain surrounding the Marines erupted like a living organism.

"Every square inch of the beachhead was under methodical, deadly

fire -- like a giant sponge, every hole a separate hell," wrote historian

Bill D. Ross.

The trap had been sprung, but although Kuribayashi's troops inflicted horrific casualties, the human wave kept coming: 30,000 by the end of the day. The general's army was already outnumbered and the battle had barely started.

By Day 2, the Americans began to realize what they were up against. Despite the losses of D-Day and the symbolic fall of Mount Suribachi two days later, the bulk of the Japanese forces -- including eight infantry battalions and hundreds of tons of heavy weaponry -- were concentrated on the north of the island. Disengaging them would be an inch-by-inch war of attrition accompanied by fresh levels of savagery.

| The Marines pumped sea water and gasoline into the bunkers when flame-throwers, demolition charges and grenades failed to staunch the Japanese attacks. |

Japanese soldiers seemed to appear from nowhere

|

Time correspondent Robert Sherrod later wrote of the casualties on both sides: "They all died with the greatest possible violence. Nowhere in the Pacific War had I seen such badly mangled bodies. Many were cut squarely in half."

But as Kuribayashi knew the moment he took this mission, the material superiority of the Americans ensured that they could grind down his army. Slowly, the Marines inched toward the general's holdout near Kitano Point, eventually cutting the Japanese force in two.

There were no surrenders. The Japanese soldiers had been ordered to fight to the death, and the small number captured were unconscious or simply too exhausted to fight on.

|

U.S. planes had fire-bombed Tokyo,

killing over 100,000 people

|

On March 9 and 10 came devastating news: U.S. planes had fire-bombed Tokyo, killing over 100,000 people. Blind military duty aside, the only |

The general marshaled his forces for a final stand with 40 men in a 700 x 500-meter stretch of arid land called The Gorge.

At midnight on March 17, he sent a final telegram to Imperial Headquarters in Tokyo. "The battle faces its final phase. Since the arrival of the enemy, the spirited fighting by my officers and men has truly surprised the demons that face us." After apologizing for yielding so much vital ground, and "failing to fulfill the expectations of the Emperor," he wrote: "Now our bullets have run out and water has dried up, but we are moving on to the last-ditch counter offensive."

The attack order went out on the 25th, and Kuribayashi died the following day, most likely from shellfire. Determined to die anonymously with his men, he had removed all identifying insignia from his uniform. His body was never found -- lost, perhaps permanently, with the remains of some 10,000 others in the soft volcanic soil of Iwo Jima.

| Perhaps a fitting epitaph for this iron-willed samurai who sacrificed himself in a war he never believed in against a country he once loved can be found among his letters to Taro, in which he wrote: "The weak-willed man makes mistakes. Willpower is the essence of manhood. A man's strength is determined by the strength of his will." |

The weak-willed man makes mistakes. Willpower

is the essence of manhood. A man's strength is determined by the

strength of his will

|

The Japan Times

(C) All rights reserved

Send Corrections, additions,

and input to:

|

Visitors since

June 6, 2000 |